CORVALLIS, Ore. — Ongoing statewide wastewater testing and genome sequencing through the collaboration of Oregon State University’s TRACE-COVID-19 project and the Oregon Health Authority suggests the South African variant of the COVID-19 virus is present in Albany and Corvallis.

The South African variant of COVID-19, B.1.351, has a mutation that allows the virus to more effectively latch onto a person’s cells, so someone who is exposed to this variant is more likely to become infected. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate it spreads roughly 50% faster than the original COVID-19 virus, just like the United Kingdom variant, B.1.1.7.

With the South African, U.K. and California variants spreading in the state, COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations are rising in Oregon and public health officials are urging caution.

“This is a dangerous path, and we’ve been down it before. We know how these variants spread and we know how to stop them — through consistent masking, physical distancing, avoiding social gatherings and getting vaccinated,” said Dr. Melissa Sutton, medical director for respiratory viral pathogens at OHA. “We need the public to stay vigilant as we work to vaccinate people in Oregon.”

The South African variant is of particular concern. According to the CDC, several studies suggest this variant may have increased resistance against those vaccines, and the AstraZeneca vaccine used in other countries did not provide protection from the South African variant.

Mutations consistent with the variant were detected in consecutive wastewater samples taken from Albany on March 26 and March 31, as well as in samples taken near off-campus housing north of the Corvallis campus on April 4.

The first case of B.1.351 in Oregon was reported to public health officials in March, Sutton said, and the Oregon Health Authority reports that 10 people in the state have tested positive for the variant to date.

“Following on the heels of the individual cases, the wastewater data supports the fact that the South African strain is here in Oregon, and that it’s likely spreading,” said Brett Tyler, a principal investigator with OSU’s TRACE project and director of OSU’s Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing.

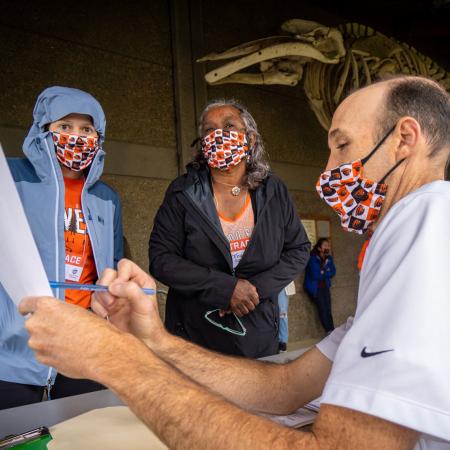

Tyler’s lab is sequencing the virus’ genome on all positive COVID-19 samples that come from wastewater and TRACE community prevalence testing. In partnership with OHA, TRACE is conducting wastewater sampling in 40 cities throughout Oregon every week to monitor the presence and concentration of COVID-19 in those cities.

The wastewater sampling and sequencing of positive samples allow public health officials to ramp up individual testing and contact tracing efforts in specific communities and neighborhoods, even when people are asymptomatic or haven’t yet been tested for COVID-19.

TRACE’s genome sequencing has been a major part of the project since last spring, before any COVID variants of concern had emerged, Tyler said.

“The foresight of OHA in supporting the statewide wastewater sampling and of TRACE to fund the sequencing from the outset meant that we were fully set up with the experience and the sequence analysis pipelines to quickly ramp this up when it became critical,” Tyler said. “The early investments by OHA and TRACE really paid off. Once the variants of concern emerged, we were right there — we had already figured out how to do all this.”

Meanwhile, other states are scrambling to catch up on implementing sequencing processes, said Tyler Radniecki, the TRACE principal investigator leading the project’s wastewater testing.

“Having this network allows us to monitor the entire state rapidly and look at these variants, even if we don’t sequence clinical samples,” Radniecki said.

OHA is supporting a new sequencing machine for OSU’s lab that will allow for faster test results for the wastewater surveillance program. However, large-scale testing of positive samples from clinical COVID-19 tests remains limited by the supply chains for reagents and other materials, Brett Tyler said.

“That’s another advantage of the wastewater surveillance: It takes fewer resources,” he said. “We can blanket the state very cost-effectively while the state gears up to do more and more clinical sequencing.”

While researchers are worried about the South African variant breaking through vaccine protection, vaccination remains one of the best ways to stop the spread of COVID-19, Tyler said.

“The vaccines may have reduced effectiveness against this strain, but they’re still a whole lot better than not being vaccinated,” he said.

This story was originally posted by the Oregon State University newsroom.