CORVALLIS, Ore. – Genetic evidence in Corvallis wastewater of the virus that causes COVID-19 has been consistently detected at moderate levels for the past month following a late July spike, said Tyler Radniecki, associate professor of environmental engineering at Oregon State University.

Currently, sewer surveillance cannot put an exact number on how many people are infected, but it can act as the “bloodhound” that sniffs the virus out, Radniecki said. The work will continue on a statewide basis for the next 30 months thanks to an Oregon Health Authority grant.

“We can monitor its rise and fall, detect priority hotspots and then alert the appropriate health authorities, medical researchers and other decision-makers who can go in and take it from there with their knowledge, skills and technologies,” he said.

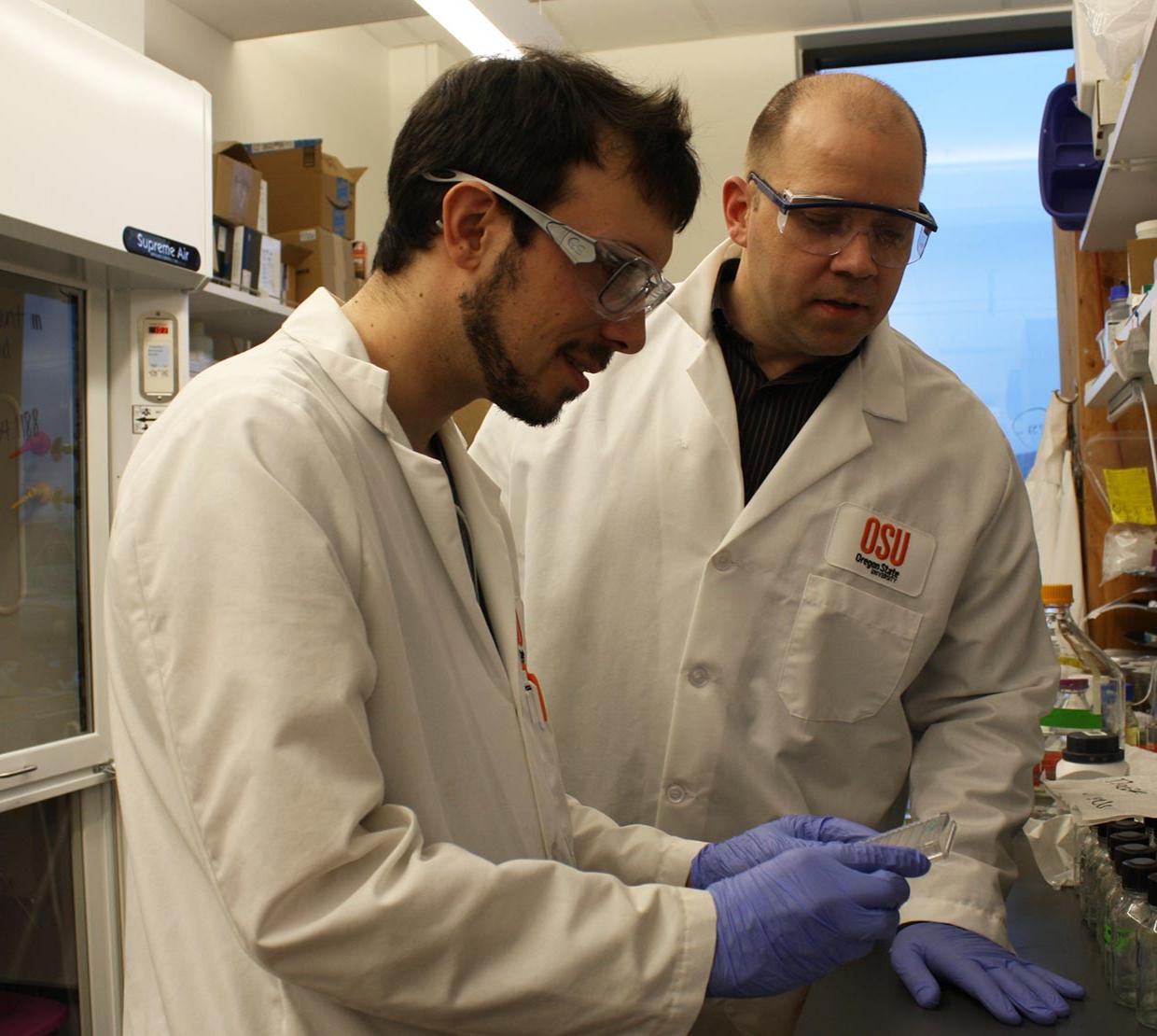

Radniecki and OSU College of Engineering colleague Christine Kelly have been leading the wastewater project – called Coronavirus Sewer Surveillance – as a component of the university’s TRACE-COVID-19 community prevalence research since late May.

Radniecki and Kelly had begun analyzing Corvallis wastewater weekly earlier in May and had only “non-detects” – results showing no detectable genetic material from SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19 – until near the end of July.

“Then we had a significant spike on July 20,” Radniecki said. “The following three weeks, we saw a drop in the viral signal but it remained detectable– meaning we could still detect it but at a lower level. That says that the virus is present in the Corvallis community at levels higher than it was this spring and early summer.”

There has been no indication that the novel coronavirus can survive as an infectious agent in sewage, Radniecki said, but RNA signatures do survive and are detectable. Oregon State has the lab capability to do the genetic testing with a turnaround time of about three days.

“Our approach overcomes the issue of asymptomatic carriers by detecting the virus from both symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers,” Kelly said. “That eliminates the delays inherent in relying on hospitalization records to confirm the appearance and disappearance of a COVID-19 outbreak.”

Radniecki and Kelly’s team will continue to sample Corvallis wastewater weekly for the next two and a half years as part of a $1.2 million Oregon Health Authority-funded effort to monitor sewage around Oregon.

In addition, during fall term at OSU the researchers will sample wastewater from the university’s campuses in Corvallis and Bend, and at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, focusing on sewage from university-owned student housing and other buildings.

“The goal there is to identify hotspots within the university community for follow-up testing and to provide a general sense of the trends of the virus at the university locations,” Radniecki said.

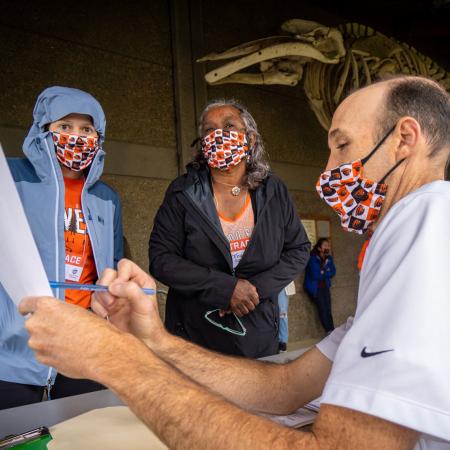

TRACE-COVID-19’s door-to-door sampling will resume in Corvallis the weekend of Sept. 12-13. Over four weekends of sampling in late spring, TRACE testing suggested a community prevalence of between one and two COVID-19 cases per 1,000 people.

This story was originally posted by the Oregon State University newsroom.